Android's AccessibilityService: A Single Toggle to Total Device Control

Table of Contents

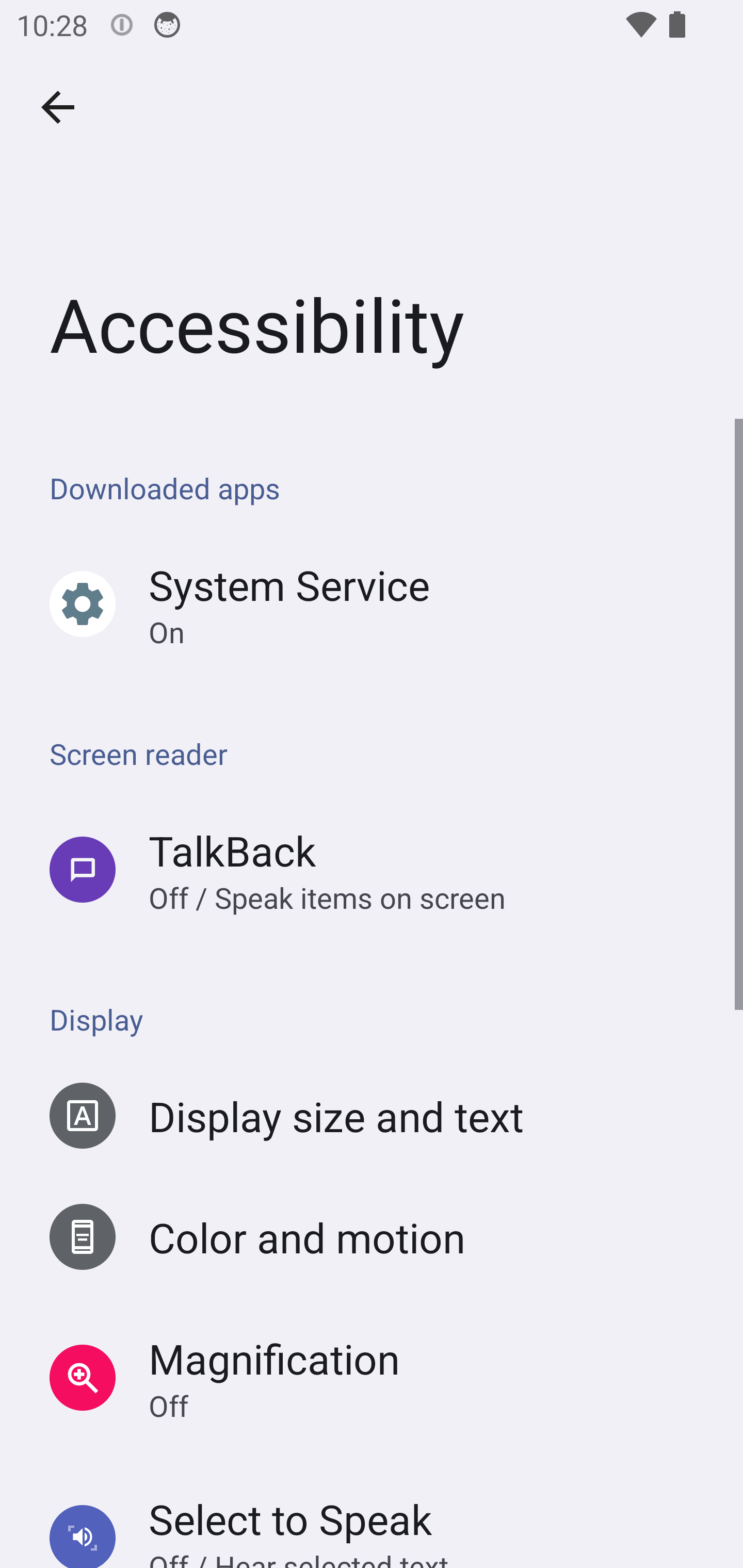

A user installs an APK. Maybe it was sent by someone they trust. Maybe it looked like a system update. Maybe it was a “parental monitoring” app they found online. Whatever the story, the app opens and asks them to enable an accessibility service. One toggle in Android Settings.

They flip it.

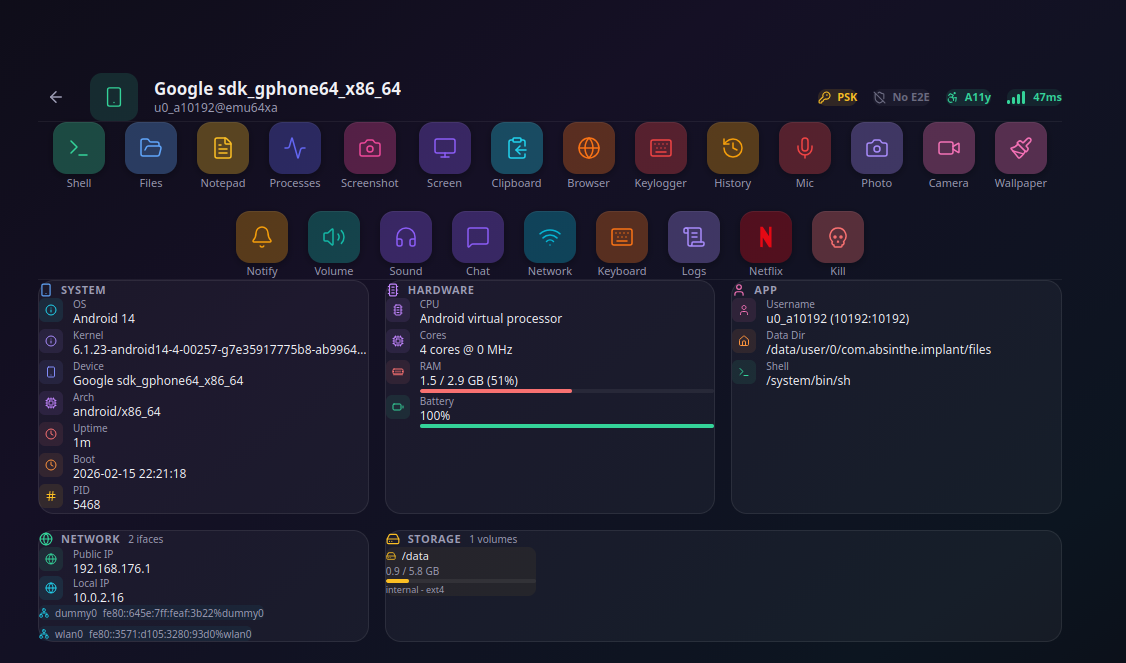

Within 2.4 seconds, the app has silently granted itself every dangerous permission on the device - camera, microphone, location, contacts, storage, phone, SMS. No dialog appeared long enough to read. No confirmation was required. The phone is now fully compromised: screen capture, keylogging, gesture injection, file access, real-time touch control, browser history, and a full Linux terminal running inside the app’s sandbox. No root. No exploit. No jailbreak. No 0-day. One toggle.

I built this. From scratch. Not because I wanted to create stalkerware, but because after years of reading security articles that say “AccessibilityService can be abused” without ever showing what that actually means in practice, I decided to find out. What I found is worse than anything I’d read. The existing coverage - even from mobile security companies - is absurdly superficial. They mention the risk in a paragraph and move on, as if a single API granting god-mode over an Android device is a footnote.

It’s not a footnote. It’s a $145 million industry. And nobody is explaining it properly. This post fixes that.

What AccessibilityService Actually Gives You

The Android AccessibilityService API was designed for users with disabilities. Screen readers, switch access devices, voice control - these are legitimate use cases that require deep access to the UI layer. The problem is that “deep access to the UI layer” translates directly into complete device control. There is no intermediate state. You either have the service enabled or you don’t, and if you do, here is exactly what the API exposes.

The UI Tree - Reading Everything

An active accessibility service receives a live, structured representation of everything displayed on screen. Every text field, every button, every label, every image description. Not just in the foreground app - in all active windows simultaneously. The service can request the FLAG_RETRIEVE_INTERACTIVE_WINDOWS flag to access system dialogs, notification panels, and overlay windows from other apps.

Each node in this tree carries its resource ID - the identifier that the app’s developer assigned in their layout XML. This means an attacker doesn’t need to guess what an element is. They can target com.whatsapp:id/conversation_contact_name to extract who the victim is chatting with, or com.android.chrome:id/url_bar to read the current URL. It’s not pattern matching. It’s direct, named access to the internal structure of every app on the device.

The service also receives real-time events. TYPE_VIEW_TEXT_CHANGED fires on every keystroke, with the full content of the input field. TYPE_WINDOW_STATE_CHANGED fires when the user switches apps or navigates to a new screen. TYPE_WINDOW_CONTENT_CHANGED fires when page content updates - a new message in a chat, a page load in the browser, a notification appearing.

This isn’t surveillance through a camera. It’s surveillance through the UI itself. Every app on the device becomes transparent.

Gesture Injection - Touching Everything

The dispatchGesture() API lets an accessibility service synthesize touch events anywhere on the screen. Taps, swipes, long presses, pinch-to-zoom, multi-finger gestures. The system treats these identically to real finger touches. There is no flag, no marker, no way for the receiving app to distinguish a synthesized gesture from a human one.

This works on system dialogs. It works on the permission controller - the system component responsible for showing “Allow” / “Deny” dialogs when an app requests camera access. PermissionController sets filterTouchesWhenObscured, which blocks touch events from overlay windows. But dispatchGesture() isn’t a touch from an overlay - it’s an accessibility action dispatched by the system itself. The filter doesn’t apply.

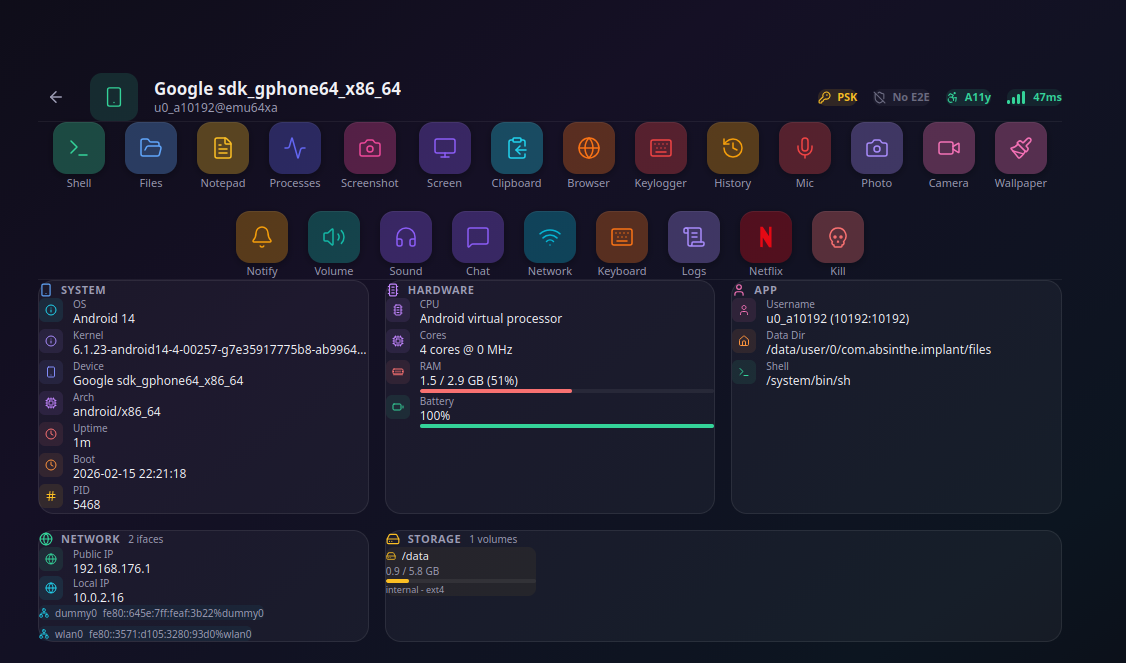

The continuing stroke API allows real-time finger-following: touch down at coordinates, move through a path, lift up. Combined with screen capture, this enables full remote control of the device - an operator on a web panel dragging their mouse, with the gesture replayed in real time on the victim’s phone.

Beyond individual gestures, the service has access to over 30 global actions: HOME, BACK, RECENTS, NOTIFICATIONS, QUICK_SETTINGS, POWER_DIALOG, LOCK_SCREEN, TAKE_SCREENSHOT, and more. These are system-level actions that no regular app can perform.

Overlay Windows - Showing Anything

An accessibility service can create windows of type TYPE_ACCESSIBILITY_OVERLAY. These float above everything - above other apps, above the status bar, above the navigation bar, above system dialogs. No SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW permission is needed. The accessibility service IS the permission.

These overlays can be fully transparent, semi-transparent, or fully opaque. They can be non-touchable and non-focusable, meaning the user can still interact with the app beneath them without knowing the overlay exists. Or they can be opaque and cover the entire screen, showing whatever the attacker wants the victim to see.

This is the mechanism behind banking trojans that display a fake login page over the real banking app. It’s also the mechanism behind the screen-freeze trick I’ll describe later, where the victim’s screen appears to pause while the attacker performs actions behind the overlay.

Screenshots - Seeing Everything

Starting with Android 11 (API 30), the AccessibilityService gained takeScreenshot(). This captures the current screen contents directly from the hardware buffer. No MediaProjection session required. No “Screen recording” notification in the status bar. No toast. No indicator of any kind. The capture is completely silent.

The captured frame comes as a HardwareBuffer with full color space information, allowing GPU-accelerated post-processing before encoding to JPEG. This means the attacker can stream the victim’s screen at multiple frames per second with adjustable quality and resolution - effectively a remote desktop, invisible to the user.

For earlier Android versions that lack takeScreenshot(), the same service can initiate a MediaProjection session. Android normally shows a confirmation dialog for this, but the gesture injection capability clicks through it automatically.

Attack Scenarios: From Toggle to Total Control

Everything above is documented Android API. What follows are the attack chains these capabilities enable when combined. These are not theoretical - I built and tested each one.

Silent Permission Escalation (2.4 Seconds)

When an Android app requests a dangerous permission - camera, microphone, location - the system shows a dialog with “Allow” and “Deny” buttons. This dialog is the entire security model for runtime permissions. The idea is that the user reads the request and makes an informed decision.

An accessibility service makes this dialog irrelevant.

The flow works like this: the app calls requestPermissions() for all its dangerous permissions. Android shows the first dialog. The AccessibilityService detects the dialog appearing through the event stream, locates the “Allow” button, and taps it. The dialog dismisses. Android shows the next one. The service taps “Allow” again. This repeats for every permission.

There are two strategies for finding the button. The first is tree-based: the service reads the dialog’s accessibility tree, finds the button node by its known resource ID (these IDs are consistent across Android versions and manufacturers), and either triggers ACTION_CLICK on the node or dispatches a gesture tap at its coordinates. This works on most devices.

The second strategy handles an edge case: on some recent Android versions using Jetpack Compose for the permission UI, the accessibility tree of the dialog is partially inaccessible from the service. In this case, the service falls back to blind scanning. It detects the dialog window by its bounds (centered on screen, smaller than full screen, focused), then taps progressively from top to bottom in fixed increments. On Android, the “Allow” button is always positioned above the “Deny” button. After each tap, the service checks whether a permission was granted. If yes, it remembers the Y-offset that worked and reuses it for the next dialog.

For comparison: GhostSpy, a known Android RAT analyzed by CYFIRMA, uses two approaches. Their tree traversal method (getAutomaticallyPermission) recursively walks the accessibility node hierarchy looking for android.widget.Button elements whose text matches hardcoded permission prompts in several languages - “Allow”, “While using the app”, “Permitir”, “iptal”, “取消”. Their blind tap method (AllowPrims14_normal) taps from 45% to 90% of screen height with sleep intervals between each attempt.

CYFIRMA describes these sleep intervals as:

“Sleep intervals mimic human behavior, reducing detection risks.”

Having built the same thing, I can say this interpretation is wrong. The delays aren’t stealth - they’re necessity. Here’s why it’s actually slow:

- Tree population delay: when a permission dialog appears, the accessibility tree isn’t immediately available. The service has to wait for

TYPE_WINDOW_STATE_CHANGED, then request the root node, then the tree has to be fully populated by the system. On some devices this takes 200-500ms per dialog. - Settings transition animations: Android animates dialog appearance (fade in, slide up). The tree nodes exist but their bounds aren’t final until the animation completes. Tapping during the animation hits the wrong coordinates.

- Sequential tree parsing:

getAutomaticallyPermissionrecursively iterates every node in the tree, checking each one’s class name and text content against the hardcoded list. On a complex dialog with 30+ nodes, this adds latency per permission. - Language fragmentation: the hardcoded strings cover English, Spanish, Turkish, and Chinese, but miss hundreds of other locales. On a French, German, Arabic, or Korean device, the tree traversal finds nothing and falls back to blind tapping - which itself has arbitrary sleep intervals between attempts because without the tree, GhostSpy has no way to confirm whether a tap succeeded other than waiting and trying the next position.

The result is approximately 18 seconds for a full permission set. The approach described in this post sidesteps all of these: no tree parsing, no hardcoded text, no language dependency, no sleep intervals. It fires dispatchGesture() at computed coordinates, checks checkSelfPermission() immediately after each tap, and moves to the next permission the instant one is granted. 2.4 seconds for the same permission set (camera, microphone, location, storage, contacts, phone).

The permission dialog is security theater. Its entire purpose is informed consent. An accessibility service bypasses that consent at a speed the user cannot physically perceive.

And here’s the part that makes mitigation nearly impossible: even if Android randomized the position of the “Allow” and “Deny” buttons, the service would just check checkSelfPermission() after each attempt and retry until the permission is granted. The button moves. The service tries again. The loop is trivial.

Contextual Keylogging

Every time the user types a character, TYPE_VIEW_TEXT_CHANGED fires with the full text content of the input field and the package name of the app. This alone is a keylogger. But raw keystrokes aren’t very useful without context.

The service enriches each keystroke event with three layers of context:

First, the app identity. The package name resolves to a human-readable label via PackageManager - “Instagram” instead of com.instagram.android.

Second, the screen context. The service reads the current screen’s toolbar and header elements to determine where in the app the user is. For messaging apps, this means the conversation name - the person the victim is talking to. The service maintains a registry of per-app parsers that extract the contact name from the accessibility tree using known resource IDs or structural heuristics. How well this works depends entirely on the app - some make it trivial, others fight back. I tested 14 messaging apps on a real device; the results are in the next section.

Third, the UI tree dump. A compact snapshot of the visible node hierarchy around the input field, providing structural context that can disambiguate input fields on the same screen.

The result isn’t a stream of characters. It’s a structured log: “The user typed ‘see you tonight’ in WhatsApp, in a conversation with ‘Marie’, at 14:32:07.”

This is exactly what FlexiSpy, mSpy, and other commercial stalkerware sell as their “IM capture” feature - the ability to read messages from WhatsApp, Instagram, Telegram, and other apps without access to the app’s database. FlexiSpy’s leaked source code (from the 2017 hack of their parent company) reveals that their original approach used FileObserver on app SQLite databases, which required root access. Their non-root fallback? AccessibilityService. Same approach. Same API.

Silent Screen Capture and the See-Through Overlay

The takeScreenshot() API captures the screen silently - no notification, no toast, no visual indicator. This alone enables remote screen viewing. But there’s an interesting problem when you combine it with overlays.

If the service displays an overlay window (for visual effect, a fake screen, or anything else), the overlay appears in the screenshot too. The operator sees their own overlay instead of what’s underneath.

The solution exploits how alpha compositing works. The service creates a TYPE_ACCESSIBILITY_OVERLAY covering the full screen, but sets the window’s alpha to 0.99 instead of 1.0. To the victim, the overlay is visually opaque - 99% opacity is indistinguishable from 100% to the human eye. But the screenshot captures the composited frame, which contains 1% of the underlying screen content blended into the overlay.

That 1% is invisible in a normal JPEG. But apply a GPU color matrix that multiplies all RGB channels by 20x (clamped at 255), and the underlying screen content appears clearly in the processed image. The operator sees through the overlay. The victim sees a solid screen. Both are looking at the same frame, processed differently.

This technique allows the operator to monitor the victim’s screen in real time while the victim sees whatever the operator wants them to see - a fake “system update” screen, a black screen suggesting the phone is off, or an animated loading spinner.

Stealth Network Toggle

Sometimes the operator needs the device online, but the victim has disabled WiFi or mobile data. Toggling it through Android Settings would be visible. The accessibility service can do it invisibly.

The sequence:

- Capture a screenshot of the current screen

- Display that screenshot as a full-screen opaque overlay - the victim’s display appears frozen

- Trigger

GLOBAL_ACTION_QUICK_SETTINGStwice to fully expand the Quick Settings panel (behind the overlay, invisible to the victim) - Traverse the Quick Settings accessibility tree, find the WiFi or Mobile Data tile by keyword matching on its label

- Tap the tile to toggle it

- Dismiss the notification shade

- Remove the freeze overlay

Total execution time: approximately 2 seconds. The victim experiences what feels like a brief screen freeze - indistinguishable from a moment of UI lag that happens on any phone. They’d never suspect their WiFi was just turned on.

Device Admin Lock-in

Android’s Device Administration API lets apps prevent uninstallation and perform remote wipes. Normally, activating device admin requires explicit user confirmation through a system dialog. The accessibility service clicks “Activate” automatically.

Once activated, the combination of device admin and accessibility service creates a removal-resistant loop:

- If the victim navigates to the Device Admin settings page, the service detects it and immediately presses HOME

- If the victim somehow reaches the deactivation dialog, the service navigates away before they can tap “Deactivate”

- If device admin is disabled through ADB or another method, the

onDisabled()callback in the DeviceAdminReceiver immediately requests re-activation, and the accessibility service confirms it

The victim cannot remove the app through the normal UI. They’d need ADB access (a USB cable and a computer with developer tools) or a factory reset.

Self-Hiding

After initial setup, the app disables its own launcher activity alias through PackageManager.setComponentEnabledSetting(). The icon disappears from the app drawer. The app still runs - it’s just not visible in the launcher.

It remains listed in Settings > Apps, but the accessibility service monitors for navigation to its own App Info page. If the victim somehow finds the app in the list and opens its details, the service detects the page (by checking for the app’s name near a “Force stop” button) and immediately triggers GLOBAL_ACTION_HOME. The settings page closes before the victim can interact with it.

The app restarts automatically on boot via BOOT_COMPLETED broadcast. Even if force-stopped, the next reboot brings it back.

Browser History Exfiltration

The service maintains a list of known browser package names - Chrome, Firefox, Brave, Edge, Opera, Vivaldi, Kiwi Browser. When a TYPE_WINDOW_STATE_CHANGED or TYPE_WINDOW_CONTENT_CHANGED event comes from one of these packages, the service reads the URL bar content by finding the node with the browser’s known URL bar resource ID.

Every page navigation, every search query, every URL visited across every installed browser - captured in real time. No need to read browser databases or intercept network traffic. The URL is right there in the accessibility tree.

How Messaging Apps Expose (or Protect) Their UI

The contextual keylogging described above relies on parsing each app’s accessibility tree to extract who the victim is talking to. To build the parser registry, I dumped the UI tree of 14 messaging apps on a real device (Vivo V2041, Android 13) using uiautomator and analyzed what each app exposes to the accessibility layer.

To be clear: the parsers are syntactic sugar. The raw accessibility tree already contains everything - messages, contact names, timestamps, read receipts, reactions. An operator can dump the full tree (300 nodes max) and read it with their eyes in seconds, or feed it to an LLM for structured extraction. The parsers just automate this for real-time display in the panel. What matters is not the parsing logic but what the tree exposes in the first place.

There’s an even more radical approach that eliminates parsing entirely: visual tree rendering. Every node in the accessibility tree carries its screen coordinates (bounds), text content, and description. An attacker can reconstruct the screen layout by rendering each node as a positioned rectangle with its text - no screenshot needed. This technique is used by banking trojans to bypass FLAG_SECURE, which blocks takeScreenshot() and MediaProjection but does not block accessibility tree reading. The attacker gets a visual representation of the screen from the tree alone, defeating the one mitigation designed to prevent screen capture.

The results reveal a clear spectrum - from apps that hand everything over on a silver platter to one app that makes meaningful efforts to resist.

The Majority: No Protection

Most apps expose stable, named resource IDs for every meaningful UI element. An attacker writes a one-line lookup and gets the contact name, message content, timestamps, and read receipts. Here’s what the accessibility tree gives up for free:

| App | Contact Name Resource ID | Messages Readable | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

conversation_contact_name | Yes | Clean IDs for everything | |

| Signal | title | Yes (conversation_item_body) | Full conversation history in tree, with quoted messages and reactions |

messaging_toolbar_title | Yes | Clean IDs | |

chat_title | Yes (message_text) | Sender names via message_username | |

| Mattermost | navigation.header.title | Yes (markdown_paragraph) | Full markdown content, reactions with emoji, sender names |

| Tinder | toolbarTitle | Yes (inboxMessageTextContent) | Full message history with timestamps |

| Slack | channel_name | Yes | Channel and DM names |

| Session | pro-badge-text | Yes (bodyTextView) | Full message history |

Writing a parser for any of these apps is trivial - a single resource ID lookup returns the contact name. No heuristics, no guessing, no structural analysis. The IDs are stable across app versions and consistent across devices.

Signal deserves special attention here. It’s a privacy-focused messenger that implements end-to-end encryption, and its UI tree is the most readable of any app tested. Every message is in a conversation_item_body node with its full text. Quoted messages appear in quote_text. Reactions show as reactions_pill_emoji. Read receipts are in footer_delivery_status. The contact name is in a title node. An accessibility service can reconstruct the entire visible conversation without taking a screenshot.

Snapchat: Partial Obfuscation

Snapchat attempts to obfuscate its resource IDs. Most are replaced with 0_resource_name_obfuscated - a clear sign of intentional stripping during the build process. But the obfuscation is inconsistent. Several key elements leak through with their original IDs: chat_message_list, chat_input_text_field, start_audio_call, start_video_call, chat_input_bar_camera, chat_note_record_button, mention_bar.

The contact name appears in a non-obfuscated TextView in the toolbar area - the last TextView before the chat_message_list RecyclerView. Chat messages are fully readable: each message entry includes the sender name in uppercase ("LUCAS SCHNELL" or "MOI") followed by the message text as plain text nodes. Snap envelopes (photo/video snaps) show as snap_envelop markers with status text (“Opened”), but the red/blue/purple color coding that distinguishes snap types is purely visual and not exposed in the accessibility tree.

The effort is there, but the gaps make it almost as easy to parse as an unprotected app.

Messenger: Full ID Obfuscation, But Leaky Metadata

Facebook Messenger goes further than Snapchat. Every single resource ID in the app is obfuscated to (name removed). There are no stable IDs to anchor a parser on. This is a deliberate and comprehensive stripping of all resource identifiers.

However, the contact name still leaks through the content-desc attribute of a Button element in the toolbar. The format is consistent: "ContactName, Chat details" where “Chat details” is localized. Splitting on the comma extracts the name. Message content is also fully readable through content-desc attributes on ViewGroup elements - each message bubble includes its full text and sender in its accessibility description.

Messenger’s defense breaks the simple resource ID approach, but the content-desc fallback means the data is still accessible with slightly more effort. The parser needs structural pattern matching instead of named lookups, but the information is still there.

Discord: Obfuscated Header, Clean Messages

Discord presents an interesting split. The conversation header has no useful resource ID for the channel or DM name. But the input field (chat_input_edit_text) contains a hint like "Message @username" or "Message #channel" - the @ and # prefixes are consistent across all languages, making extraction trivial regardless of locale.

Meanwhile, the actual message content uses clean, stable resource IDs: author_name, timestamp, reply_text, reply_author_name. Every message in the visible conversation is fully readable with sender attribution and timestamps. Discord protects the header but exposes the entire conversation body.

X (Twitter): Zero IDs, Full Content

X has migrated to Jetpack Compose and exposes zero resource IDs in its accessibility tree. Every element is a generic android.view.View or android.widget.TextView with no named identifiers. At first glance, this looks like strong protection.

But the content-desc attributes expose everything. Every message bubble contains its full content in the accessibility description: "Alice : sounds good, see you at 8. 6:57 PM." for received messages, "You : perfect. 7:10 PM. Read." for sent ones. Reactions appear as "Reactions : ❤️ 1". Quoted messages include the full original text and the reply. The contact name appears in the header as both the profile picture’s content-desc and an adjacent TextView.

The absence of resource IDs forces structural matching instead of named lookups, but the data exposure is total. X stripped the labels but left the content untouched.

Telegram: The Strongest Defense

Telegram has the strongest defensive posture of any app tested. It exposes zero resource IDs. Every view reports a generic Android framework class - android.widget.TextView, android.widget.FrameLayout, android.widget.ImageView. There are no custom class names, no Compose semantic identifiers, no named elements of any kind. The UI tree is indistinguishable from a generic Android layout with no app-specific information.

The contact name is only recoverable through a fragile structural pattern: a FrameLayout element in the toolbar area has a content-desc containing the contact name and online status separated by a newline character ("Alice\nonline"). This requires matching on the presence of a newline in a FrameLayout description - a heuristic that could easily break if Telegram changed their toolbar layout.

Message content in the tree is plain TextView nodes with no sender attribution, no timestamps, no threading information beyond the raw text. Without resource IDs to identify which node is a message versus a UI label, parsing the conversation requires positional heuristics that are inherently fragile and device-dependent.

The Signal Paradox

The contrast between Signal and Telegram is striking.

Signal implements end-to-end encryption by default, uses the Signal Protocol (considered the gold standard for secure messaging), and has been audited by third-party security firms. It’s the messaging app recommended by security professionals worldwide. But its accessibility tree is an open book - clean resource IDs for every element, full message content, sender names, timestamps, read receipts, reactions, quoted messages. An accessibility service can silently read the entire visible conversation.

Telegram is regularly criticized for not using end-to-end encryption by default (only “Secret Chats” are E2E encrypted; regular chats use client-server encryption). Security researchers have questioned its cryptographic choices for years. Yet it’s the only messaging app that makes meaningful efforts to resist endpoint surveillance via the accessibility layer.

Encryption protects data in transit. Accessibility service abuse happens at the endpoint, where the message is already decrypted and rendered on screen. When an accessibility service can read conversation_item_body directly from Signal’s UI tree, the end-to-end encryption that protected that message across the network is irrelevant. The message arrived encrypted and is now displayed in plaintext in a named, easily queryable node.

It reveals a blind spot in how we think about messaging security. The threat model stops at the network layer. Nobody asks “what happens when the message is on screen?” The answer, for 13 out of 14 apps tested, is: anyone with an accessibility service can read it.

Stealing 2FA Codes in Real-Time

The accessibility tree doesn’t just expose messaging apps. It exposes everything on screen, including authentication tokens. This is not theoretical - banking trojans have been doing it for years.

Google Authenticator stores TOTP codes for each registered account and displays them in a scrollable list. Every entry in that list is a pair of nodes with clean, stable resource IDs:

otp_name- the account label:"GitHub: alice@example.com","AWS: admin","Discord: user@mail.com"otp_code- the current 6-digit TOTP code, in plain text:"482 391"

An accessibility service can enumerate every registered account and read every active code without any user interaction. The service doesn’t need to take a screenshot, parse an image, or inject input. It reads the values directly from named nodes in the accessibility tree, the same way a screen reader would.

The attack chain is straightforward:

- The keylogger captures the victim’s password as they type it into a login form

- The service detects that Google Authenticator has come to the foreground (the victim is fetching their 2FA code)

- The service reads every

otp_codenode in the tree and matches it to itsotp_namelabel - The attacker now has both the password and the current TOTP code

This bypasses multi-factor authentication entirely. The “something you have” factor assumes the token is only visible to the person holding the device. An accessibility service breaks that assumption - the token is visible to any process that can read the UI tree.

This is a known attack vector. Cerberus was the first banking trojan documented stealing Google Authenticator codes via the accessibility API in 2019. Escobar (a rebranded Aberebot) followed in 2022, explicitly targeting Authenticator. TeaBot and SharkBot do the same. The technique is well-established in the banking trojan ecosystem.

Google’s response was isAccessibilityDataSensitive, introduced in Android 14. When set on a View, only declared accessibility tools (like TalkBack) can read its content. Google Authenticator could use this to protect the otp_code nodes. As of February 2026, it doesn’t. The codes are still in plain text, in named nodes, readable by any accessibility service.

Beyond Surveillance: The Phone as a Pentest Box

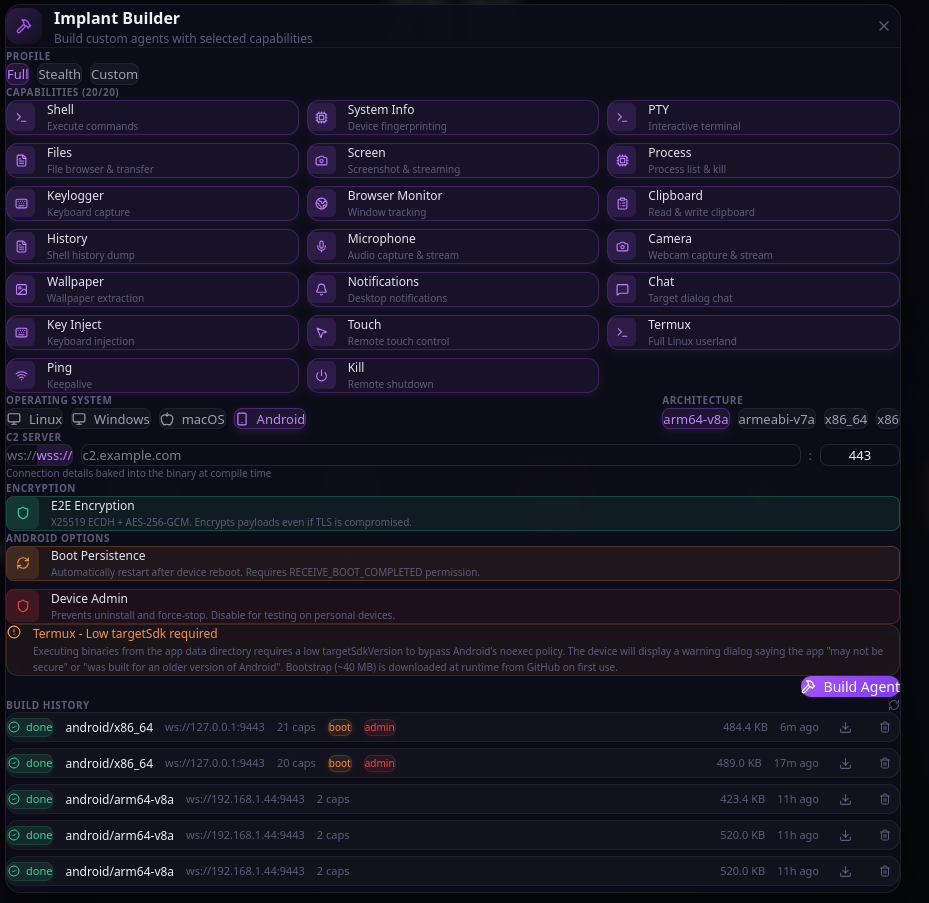

Everything described so far exists, in some form, in commercial stalkerware. Here’s where the proof-of-concept goes further than anything publicly documented.

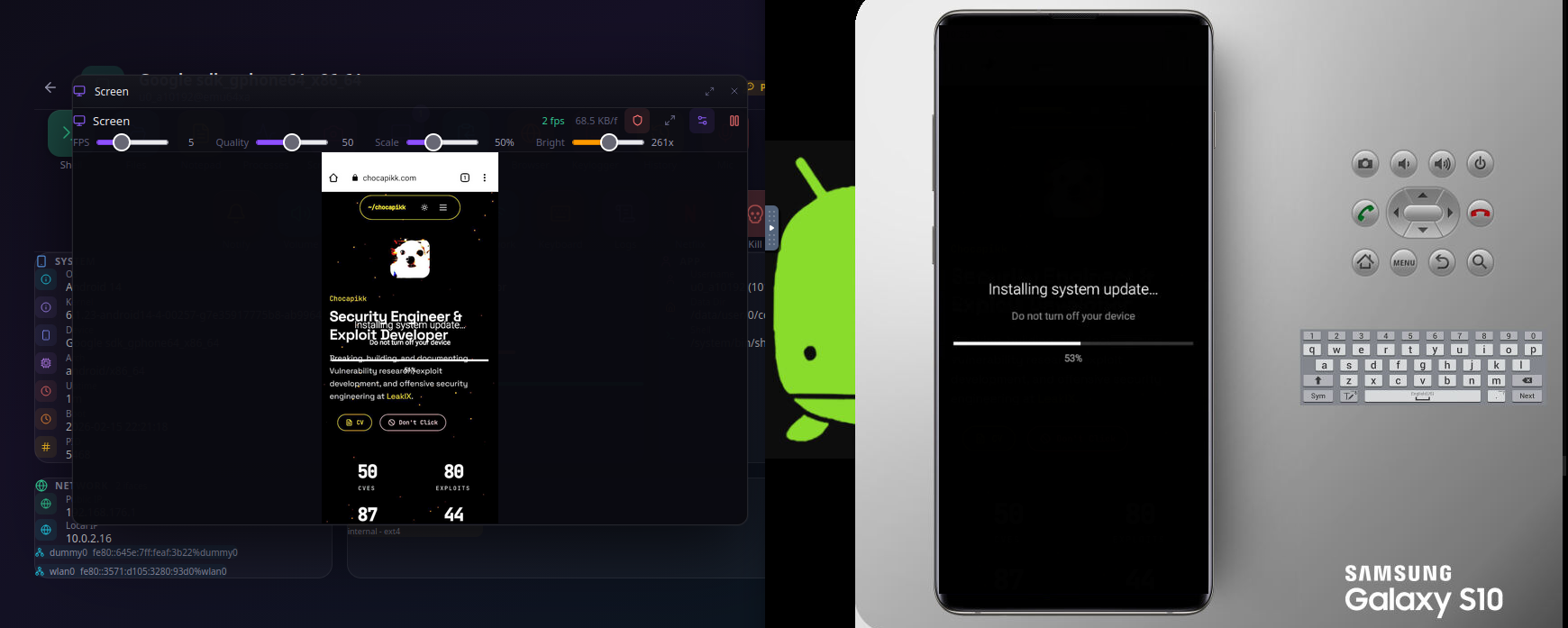

Embedded Linux Userland

Android runs on the Linux kernel, but the userspace is heavily restricted. The default shell (/system/bin/sh) is toybox - a minimal set of coreutils with no package manager, no scripting language, no network tools beyond ping. For an attacker, it’s barely functional.

But Android has a compatibility gap. The noexec restriction on app data directories - which prevents apps from executing downloaded binaries - was introduced with Android 10 (SDK 29). Apps that target SDK 28 (Android 9) or lower are exempt. They can mark files as executable and run them directly.

Android still allows targeting SDK 28. The only consequence is a generic system dialog when installing the APK:

“This app was built for an older version of Android and may not include the latest privacy protections.”

This is the same warning that appears for thousands of legitimate apps distributed outside the Play Store. Users dismiss it without reading.

With this bypass, the implant downloads a Termux-compatible Linux bootstrap at runtime - approximately 30MB from Termux’s open-source package repositories. This bootstrap includes:

- bash - a real shell with tab completion, history, scripting

- coreutils - ls, cat, grep, sed, awk, find, sort, and dozens more

- curl and wget - HTTP clients for data exfiltration or tool download

- apt - the Debian package manager, connected to Termux’s package repository

From there, the operator can install anything in the repository: nmap for network scanning, python for custom scripts, openssh for reverse tunnels, netcat for port forwarding, sqlmap for database testing. The compromised phone becomes a fully functional Linux pentest machine sitting inside the target’s network.

For context: the Termux app weighs approximately 109MB. This implant’s APK is 496KB. The Linux bootstrap is downloaded on-demand, only when the operator activates the capability. A phone on the target’s WiFi, running nmap, accessible over WebSocket, and the owner has no idea.

No Permission Required

The Termux capability requires zero Android permissions beyond INTERNET (auto-granted at install, classified as non-dangerous by Android). Binary execution happens within the app’s private data directory. The operator has a full Linux terminal running on the victim’s phone, and Android’s permission system has nothing to say about it. There is no “Allow this app to run nmap?” dialog.

The $145 Million Industry Running on a Single API

What I’ve described is not novel in concept. The stalkerware industry has been selling this for over a decade. What’s novel is demonstrating the full scope in one place, with techniques that go beyond what commercial tools offer.

FlexiSpy charges $419/year for their “Extreme” plan. In 2017, a hacker breached their parent company Vervata and leaked their source code, internal documents, and customer data. The leaked code reveals their IM capture mechanism: a FileObserver watching for changes to messaging apps’ SQLite databases, which requires root access to read. Their non-root fallback is AccessibilityService-based keystroke capture. At the time of the breach, FlexiSpy had approximately 130,000 customers and was generating roughly $400,000 per month in revenue.

Cocospy and Spyic were exposed in 2025 when a security researcher found a vulnerability that leaked 3.2 million customer email addresses. Both apps use the same backend infrastructure and the same a11y-based approach to device monitoring. 3.2 million people were paying to surveil someone else’s phone. Both apps went offline shortly after.

mSpy, Spylix, eyeZy, Hoverwatch - the market is crowded. They all advertise “no root required” and “invisible mode.” They all use AccessibilityService. They all charge between $20 and $40 per month. The global stalkerware market was valued at $145 million in 2025 and is projected to reach $265 million by 2035.

These companies brand themselves as “parental monitoring” or “employee oversight” tools. Their marketing copy talks about child safety and productivity tracking. But their feature sets - keylogging, screen capture, location tracking, call recording, social media monitoring, stealth mode - are indistinguishable from malware. The only difference is the billing model.

Google periodically removes a11y-abusing apps from the Play Store. In 2024, they updated their Developer Program Policy to further restrict AccessibilityService usage. But none of these tools distribute through the Play Store. They’re sideloaded as APKs from the vendor’s website. Play Store policies are irrelevant. The API itself is the problem, and the API isn’t going anywhere.

Why This Matters - What Should Change

Android 14 introduced isAccessibilityDataSensitive, a view property that lets apps mark specific UI elements as hidden from accessibility services. Banking apps have started adopting it to protect login fields and transaction screens. But it’s opt-in, applied per-view by each app developer. The previous section tested 16 of the most popular messaging apps in the world. None of them implement it. Not WhatsApp, not Signal, not Messenger, not Snapchat. The one app that resists accessibility tree parsing - Telegram - does so through its own resource ID stripping, not through isAccessibilityDataSensitive. Google built the mitigation. Nobody uses it. And even if they did, it’s only available on Android 14+, leaving billions of devices on older versions unprotected. It also fundamentally conflicts with accessibility itself - marking a view as “sensitive” means screen readers can’t access it either. Developers are asked to choose between security and accessibility. Most won’t choose at all.

The permission dialog is equally ineffective. When an accessibility service taps “Allow” in milliseconds, there is no informed consent. Randomizing button positions wouldn’t help - the service checks checkSelfPermission() after each attempt and retries until granted. The loop converges within seconds regardless of layout. The real fix would be to prevent accessibility services from interacting with system permission dialogs entirely. But Google has never implemented this, because switch access users and voice control users rely on accessibility services to interact with exactly these dialogs. This is the core tension that makes the problem unsolvable within the current architecture.

There is no CVE to file. There is no vulnerability to patch. The AccessibilityService API works exactly as documented. The permissions it grants are exactly the permissions Google designed it to have. The attack surface is the feature set.

Conclusion

One toggle. Everything you just read.

Everything described here uses documented, public Android APIs. The stalkerware industry has been shipping this for years. The techniques aren’t novel - only the scope of this demonstration is.

If you’re a security professional, stop treating AccessibilityService as a footnote. If you’re an Android platform engineer, the mitigations aren’t working - 0 out of 14 tested messaging apps implement isAccessibilityDataSensitive, restricted settings on Android 13+ are trivially bypassed, and Play Store policies are irrelevant to sideloaded APKs. If you’re running enterprise security, a phone with an a11y-based implant is a fully compromised endpoint on your network. Treat it accordingly.

The AccessibilityService will exist as long as Android exists. The question is whether we keep looking away.

References

Android API Documentation

- AccessibilityService - Main class reference including

dispatchGesture(),takeScreenshot(),performGlobalAction() - AccessibilityServiceInfo - Service configuration flags (

FLAG_RETRIEVE_INTERACTIVE_WINDOWS,FLAG_REPORT_VIEW_IDS) - AccessibilityEvent - Event types (

TYPE_VIEW_TEXT_CHANGED,TYPE_WINDOW_STATE_CHANGED) - AccessibilityNodeInfo - UI tree node structure

- GestureDescription / StrokeDescription - Gesture synthesis and continuing strokes

- WindowManager.LayoutParams -

TYPE_ACCESSIBILITY_OVERLAYwindow type - DeviceAdminReceiver - Device admin API

- View.setAccessibilityDataSensitive - Android 14 mitigation

- View.filterTouchesWhenObscured - Touch filtering (bypassed by

dispatchGesture) - PackageManager.setComponentEnabledSetting - Launcher alias hiding

- Intent.ACTION_BOOT_COMPLETED - Boot persistence

- INTERNET permission - Non-dangerous, auto-granted

- Behavior changes: apps targeting API 29+ - W^X / noexec on app data directories

- Restricted settings (Android 13+) - Sideloaded app restrictions

Stalkerware Industry

- Stalkerware Market Report - Future Market Insights ($145M in 2025, projected $265M by 2035)

- Meet FlexiSpy, The Company Getting Rich Selling ‘Stalkerware’ - VICE ($400K+/month revenue)

- Hacked spyware vendors haven’t warned their 130,000 customers - DataBreaches.net

- Hackers explain how they “owned” FlexiSpy - Help Net Security, 2017

- FlexiDie leaked source code - GitHub mirror

- FlexiSpy pricing analysis - Impulsec ($419/year Extreme plan)

- Cocospy and Spyic exposing phone data of millions - TechCrunch, 2025

- Cocospy stalkerware apps go offline after breach - TechCrunch, 2025

Technical Analysis

- GhostSpy: Advanced Persistent Android RAT - CYFIRMA Research

- Zimperium detects GhostSpy - Zimperium

- PixStealer: Banking trojans abusing Accessibility Services - Check Point Research

- Accessibility service malware analysis - Guardsquare

- Unveiling Accessibility Attacks on Android - Medium

- Accessibility Services mobile malware analysis - Pradeo

- Android 13 blocks accessibility for sideloaded apps - Esper.io

Google Policy

- Use of the AccessibilityService API - Google Play Developer Policy

Related Software

- Termux - Android terminal emulator (GitHub)

- Termux on F-Droid - Package listing